The black-&-white images below depict dreary scenes. They served my purpose well - I shot them for a photography class taught by a UCSD prof whose own work had a strong social-realist bent. He also had high standards and expectations and wasn’t easily impressed. When Fred Lonidier described the course’s final project I knew I had to find a strong subject, and the city I’d lived in during high school proved fitting.

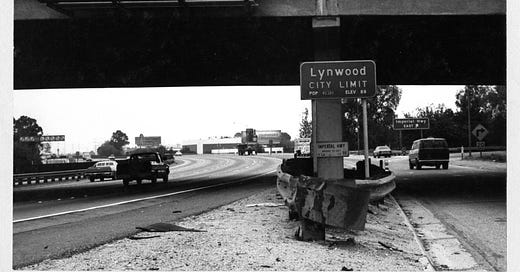

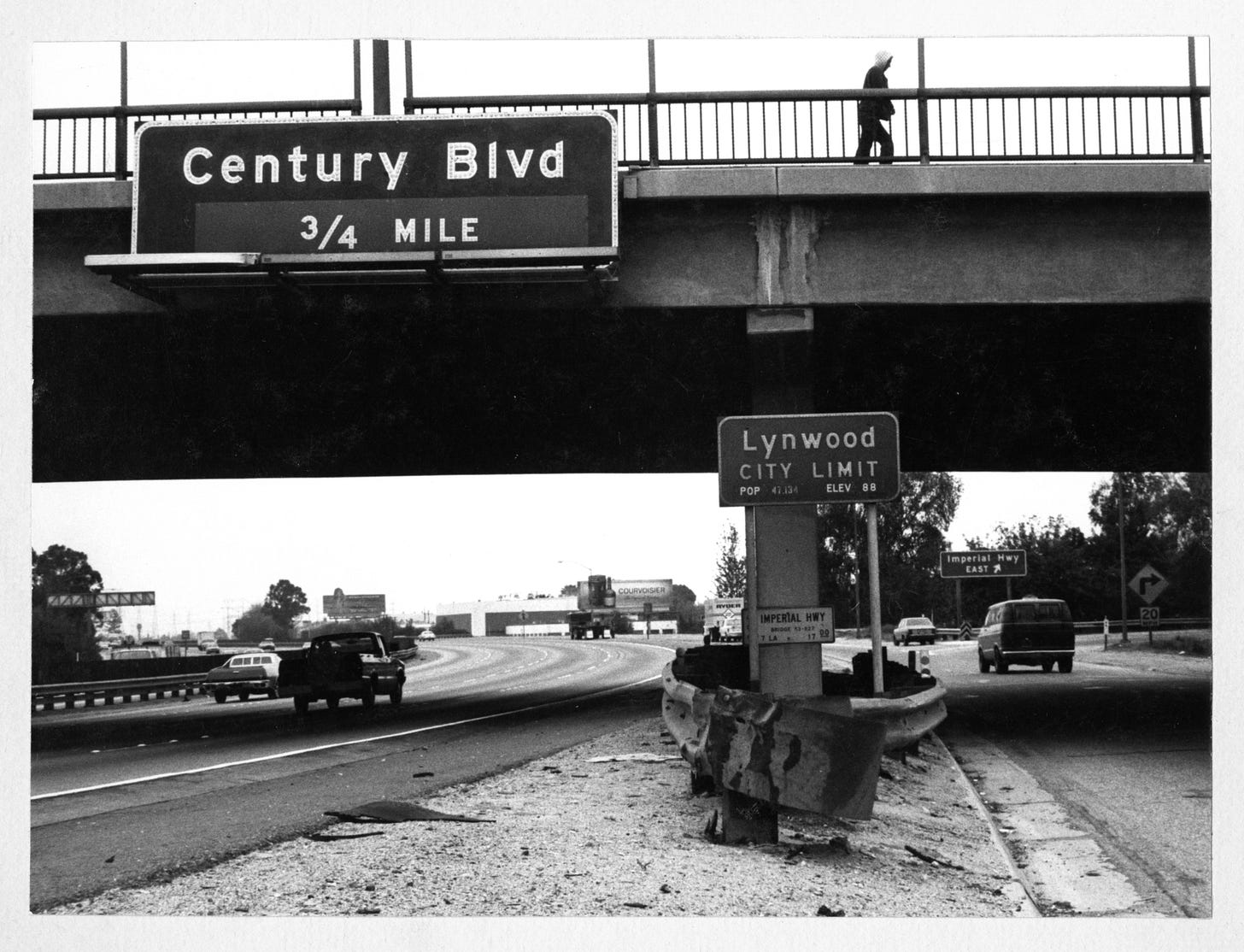

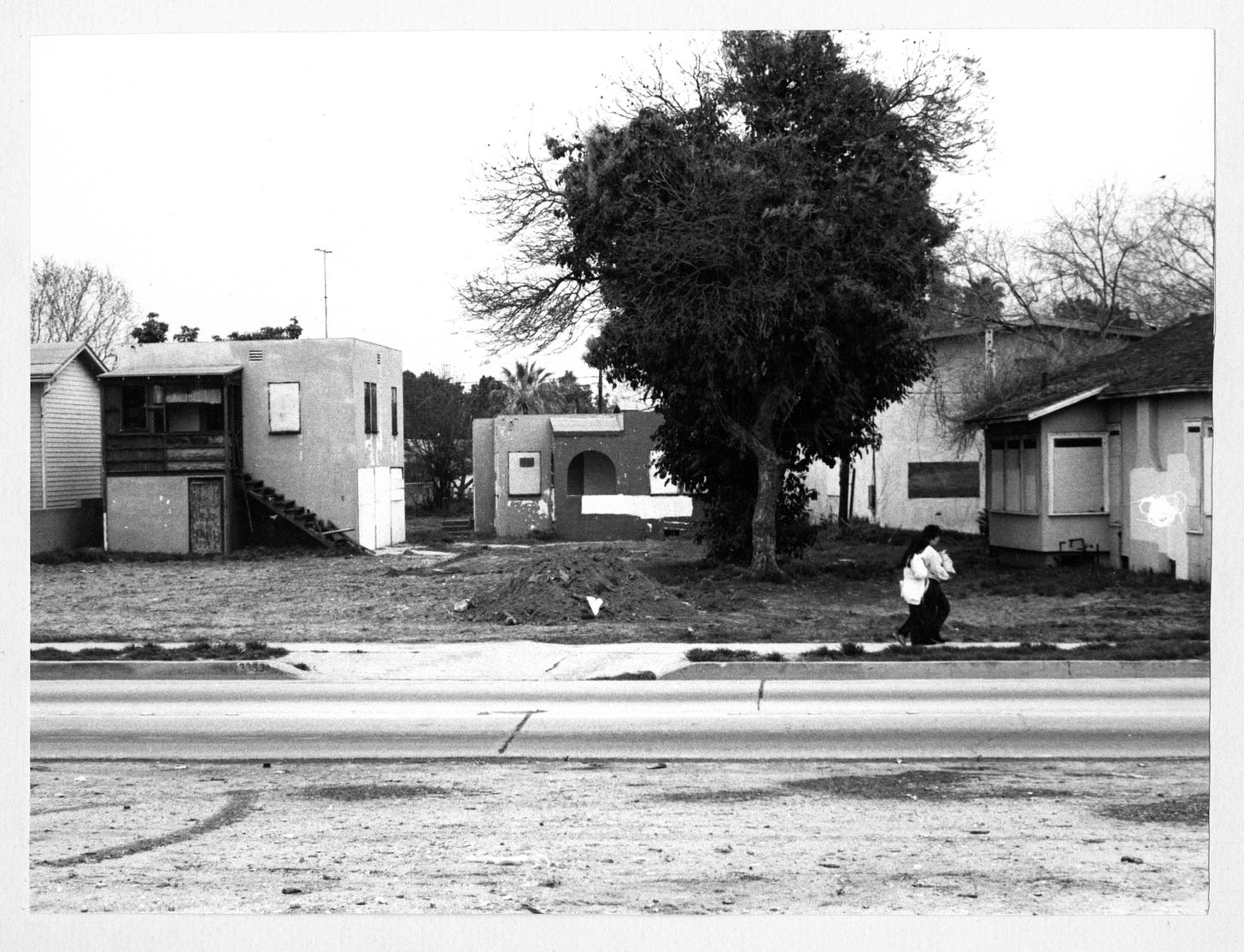

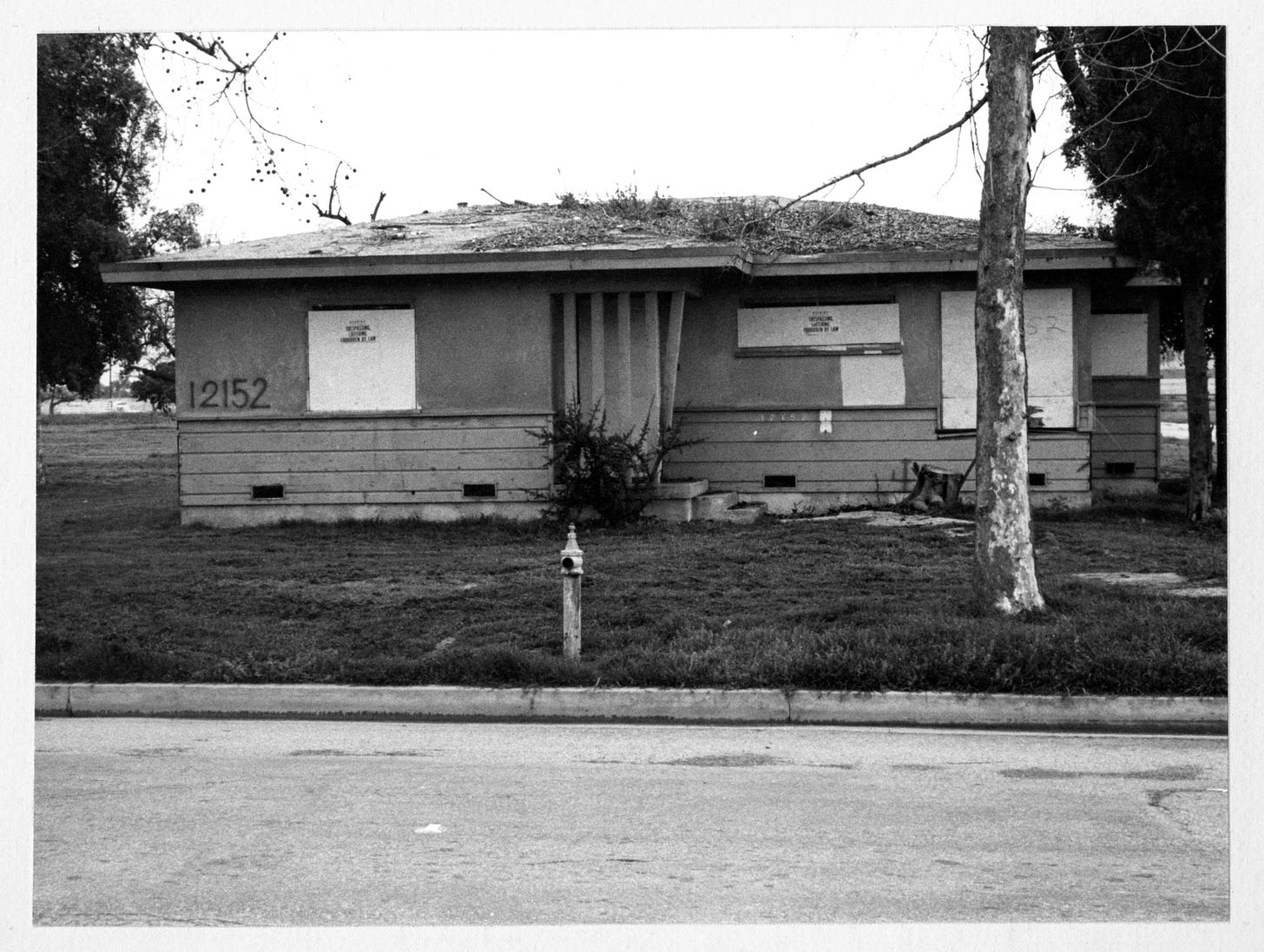

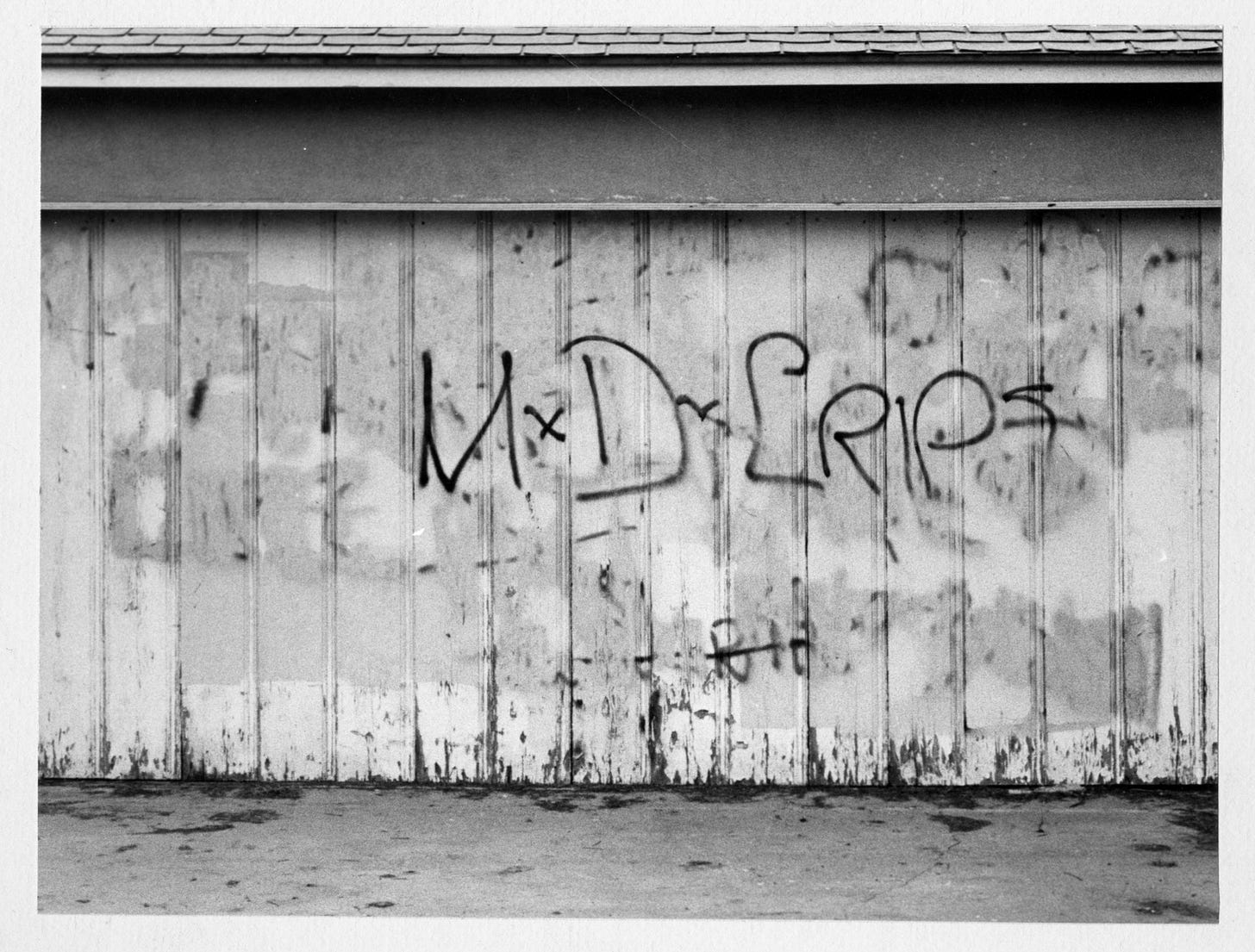

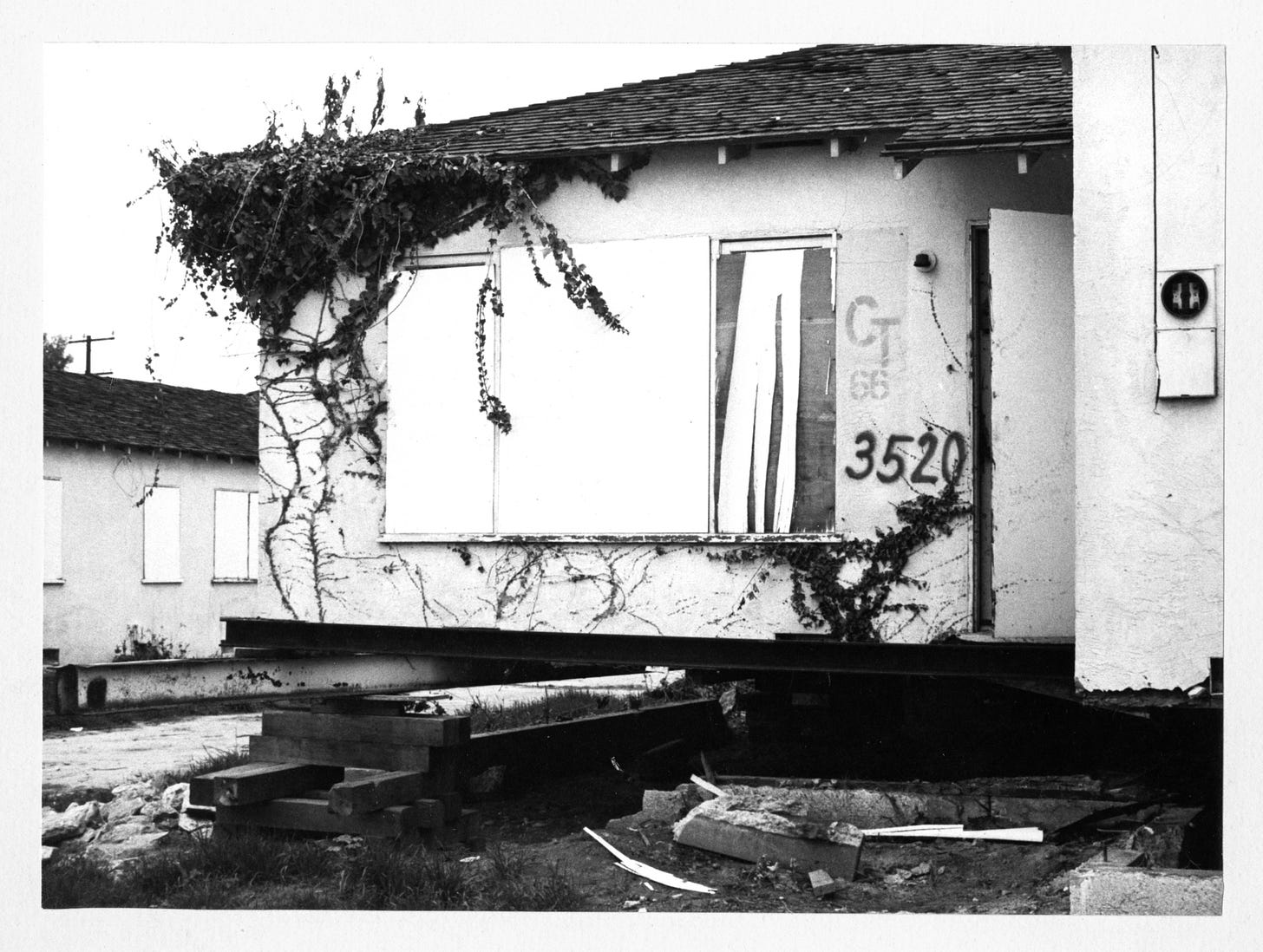

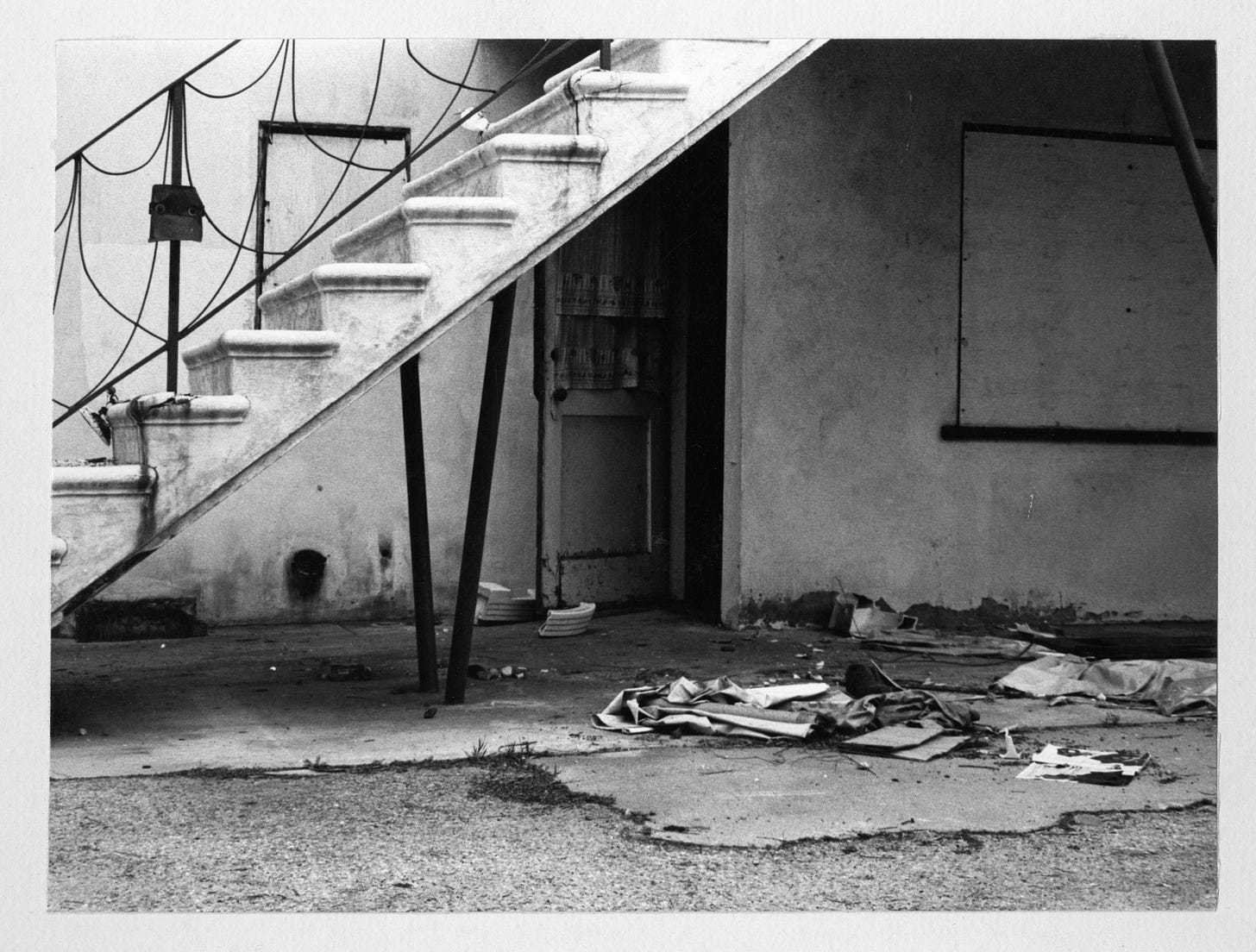

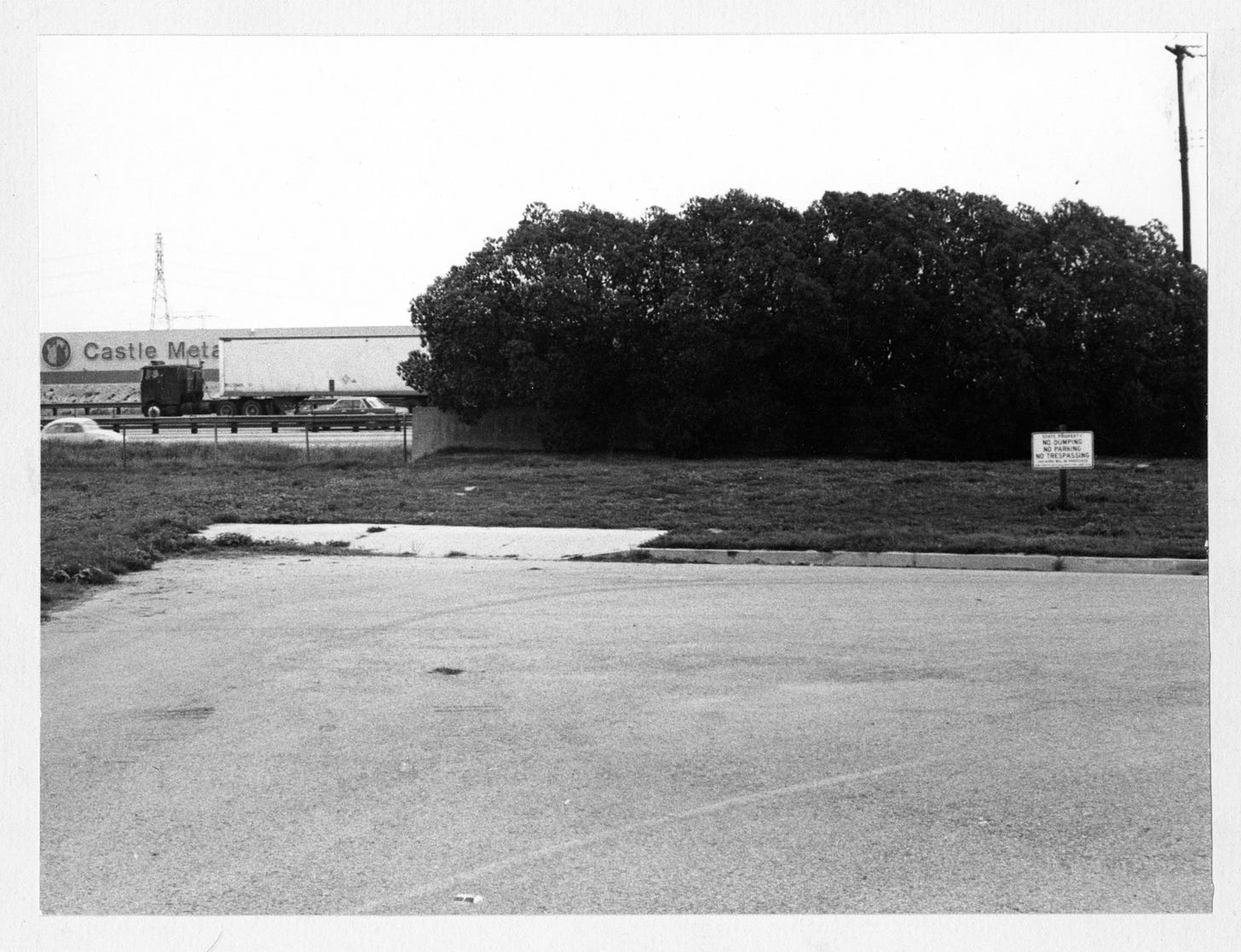

The locations were familiar. I’d ridden my bike past them many times and had wandered around grabbing random shots while taking photography as a senior at Lynwood High. They all show the effects of the stalled Century Freeway construction project, which had been halted by a lawsuit. As the court proceedings dragged on the vacant buildings that spanned the city from east to west sat awaiting their fate. The freeway project was finally completed and opened as the I-105 in the fall of 1993.

CalTrans, the state of California’s transportation authority, had begun to exercise eminent domain and buy-up property in the city in the early 1970s. By the time I moved to Lynwood in ‘74 the area of the freeway right-of-way had, for the most part, reached the state it was in when I came back to work on my college class project eight years later.

By the time Lynwood was declared an “All American City” in 1961 the former dairy farm had been paved over and expanded to match the times. Los Angeles County, was, by 1941, a kind of semi-urban agricultural paradise, and among the most productive farming areas in the nation. Then, transformed virtually overnight by wartime industrialization, it became an industrial, aeronautic and defense industry hub. Lynwood was well-positioned to participate in the boom as a centrally located bedroom community, with GM’s South Gate Assembly plant right across the city limits, Firestone and Goodyear factories a few blocks further, North American Rockwell just across the river in Downey, and McDonnell-Douglas a short hop down the freeway in Long Beach. Hollywood was the glam district, but the real economic backbone of La-La land lay on the other side of the tracks, south of the rail yards.

With its wartime boom Southern California became a powerful magnet for workers from around the country. and by the early ’60s suburban LA had entered its industrial golden age, as depression and war started to recede from memory, replaced by prosperity and continued population growth. Lynwood played its part in accommodating the newcomers, the city’s population quadrupling in the thirty years preceding its All American award - then it grew even more, reaching 43,000+ by 1970. So it’s a safe assumption that most Lynwood-ites of this era were new or very recent arrivals, mostly from the Midwest and South; also among the crowds flocking to Southern California were African-Americans looking for opportunities unavailable elsewhere. All American Lynwood was not a notably welcoming destination at the time, but it was next door to places where they could buy-in, bordering Watts to the west and Compton to the south. By the late ‘50s the latter was undergoing its own demographic shift, partly as a hangover from the severe housing shortage of the war years; one of Compton’s public housing developments was briefly home to the Bush family while the father worked in the local oil business, but they didn’t stay long.

I’d spent many years in my early childhood in a small, rural town surrounded by the wide open spaces of the Great Plains. In suburban Southern California there wasn’t much to remind me of that. I think the open spaces of the freeway corridor held some fascination for me partly because of the distances between the remaining buildings. But that was also an accident of timing - I hadn’t lived around there when it had been vital, a living neighborhood. For most it was a place to avoid. It stayed that way for two decades.

Ironically, in Lynwood the path of the Century Freeway followed the footprint of the abandoned Pacific Electric ‘Red Car’ rail system. The freeway project was, essentially, an update and replacement of it, and in Lynwood its path briefly joined the red car right-of-way. In its heyday the rail line had funneled riders from southeast LA county to downtown and rail connections to the rest of the USA at Union Station. But there wasn’t much room in the old pueblo for jet age facilities, and Los Angeles International Airport, with its signature Jetsons-styled rotating restaurant and stream of 707s hurtling out over the Pacific, was emblematic of a new era. The rail system, not yet sorely missed, must’ve seemed a worn-out relic of a less advanced time. Urban legend blaming the auto industry for its demise has since taken hold, but its ridership was on the decline when it went under. Lynwood’s station, squarely in the path of the freeway project, was preserved and is now living a second life, serving as a bus depot on Martin Luther King Boulevard at the edge of Lynwood Park.

Great article. I was born and raised in Lynwood until I left to the Navy then college and law school. I recall that old train station on Long Beach Blvd. I recall playing on many old, beautifully abandoned buildings and fields along what is now the 105 freeway. We use to walk along the train tracks on our way to what was then Montgomery Ward. Lynwood was certainly at the edge of change. A change that I wouldn’t understand until much later.

What a great story. When I got to the next-to-last picture of the old train station, I thought "Oh no, the place has been demolished!," but then I saw the following picture taken in almost the exact spot. A sweet ending.