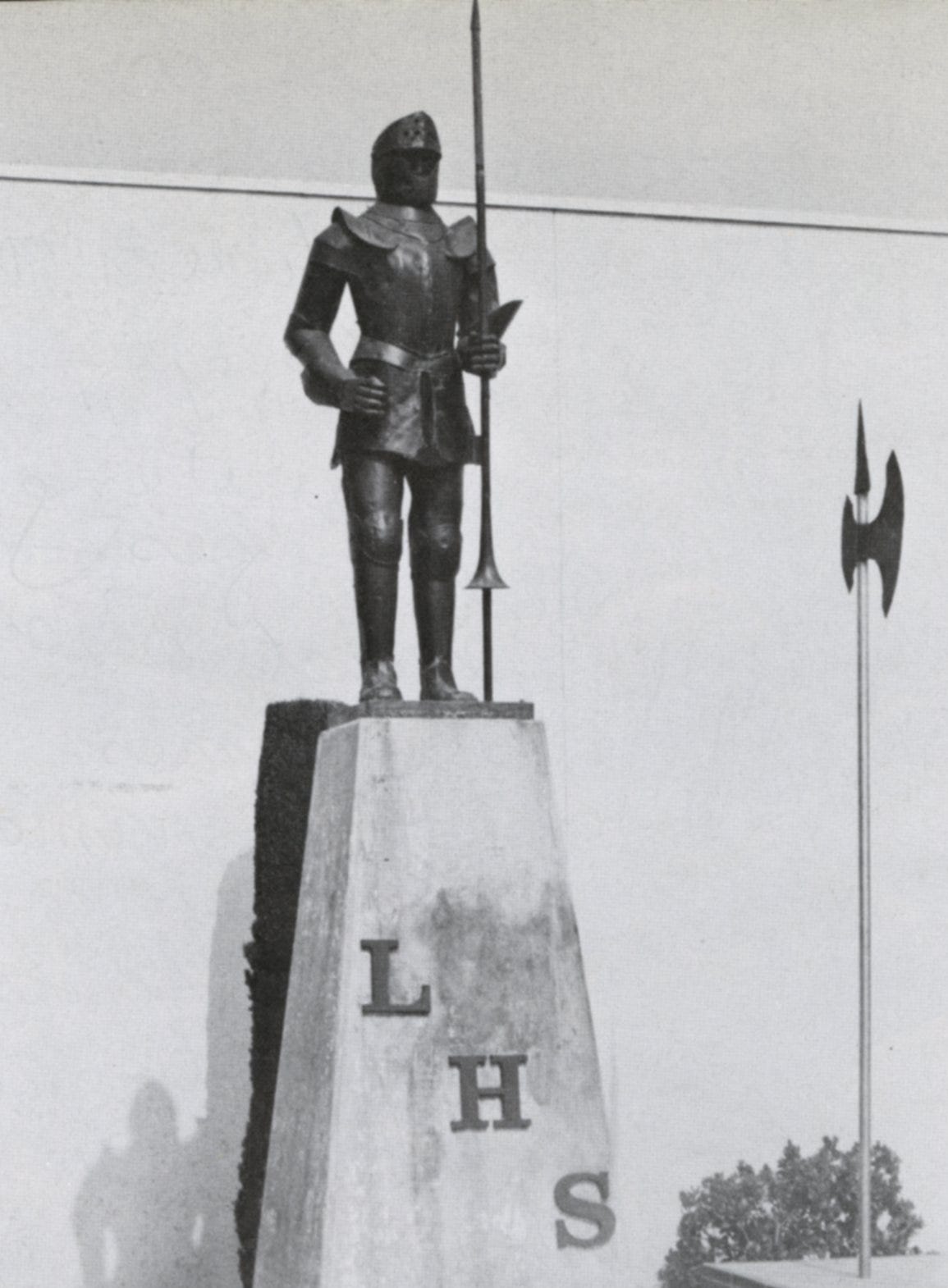

It was easy to be all-in for high school. As of Day 1, September 3rd, 1974, I lived half a block away, knew no one, and, like the school itself, was well-removed from the middle of my new ‘All American City.’ So, by default, Lynwood High School immediately became the epicenter of my 9th grade universe. As others shuffled in, out or around it, I was drawn there by the typical teenage desire to get out of the house. The campus down the block served that purpose well for four years, and would make all the difference. In that time, the mid-70s, Lynwood was in the grip of a dramatic demographic change, with attenuated freeway construction, white flight and black home-ownership transforming the city. As a transplant from the rural Midwest I never got the actual hang of surfing, but nonetheless found myself riding the wave that washed over the place. It wasn’t where I thought I’d be when I’d attended my small-town elementary school, but a couple years down the road I was ready for it to occupy center stage in my life mostly because it was so close to my new home and I didn’t have anywhere else to go.

At 14 I would’ve preferred to be back in my old town - a small and familiar place. It hadn’t had much of a social pecking order, but at least, having been elected 7th grade president, I knew I wasn’t on the bottom of it. (Then again, I’d served one of the quietest terms in 7th grade presidential history, having been quickly put in my place by our gruff class sponsor.) A couple years later, on my first day at LHS, my entry was noted by teachers in the usual routine way. I soon learned that I was too late for freshman football, a major disappointment, since the game loomed large in my adolescent mind. But the water polo team welcomed anyone who could swim. I dove-in to give it a try and discovered it required a rigorous regimen of ‘double days’ during the school week: an early AM conditioning session and an after-school team practice. I rode my bike down dark streets to the ‘Natatorium’, our off-campus pool, to get there by 6:30 AM and then pedaled back through crowds streaming toward school an hour and a half later. The routine made for a bracing start to the day. After school? Rinse, lather, repeat.

I never amounted to much in polo, but it helped me meet people. Some teammates became great friends, so three months attempting a sport I’d known nothing about was time well spent. Meanwhile I set about the bigger task of trying to locate myself in an unfamiliar setting, struck by the fact that it daily contained many more people in a couple acres than lived in the entire square mile of my old hometown. The range of niches in Southern California’s crowded and complex social fabric slowly came into focus: an early pal with a Greek last name and accent; a lanky Argentine soccer player who looked white like me but spoke no English; pretty Mexican girls with heavy eye shadow; black guys from my block on the cusp of athletic greatness; beefy guys of all races with beards and mustaches. I found myself submerged in a mass of teens of all shapes, sizes, colors - and it was 1974, so most of them had a lot of hair! At the homecoming assembly a prospective queen candidate said her most memorable moment happened the previous spring when her boyfriend was kidnapped by the SLA (the big news Symbionese Liberation Army, who’d taken Patty Hearst before that). By that alone I knew I definitely wasn’t in small town Nebraska anymore. I might’ve figured it out eventually; over the next four years Lynwood High elected white, black, Hispanic and Asian homecoming queens.

Suddenly I was in the deep end of adolescent learning, testing the strange waters of an institution bearing up under the weight of both positive and negative expectations. My new home-away-from-home would ultimately deliver a decent education by design and an invaluably unique one by accident of timing and location. While many of the white kids were being uprooted and relocated down the road in Downey or Orange County, some of the black kids actually lived in Compton, Willowbrook or Watts. Their parents wanted them in Lynwood because nearby LA and Compton schools were not meeting expectations, so the necessary ruse of a false Lynwood address was common. Anyway, the controlling factor was the availability of housing in the town, and white flight provided a ready supply. As a result much of the most valuable learning that went on at LHS - for me and many others - involved meeting and getting along with people we wouldn’t have crossed paths with otherwise. Racial tension and friction existed but didn’t come close to poisoning the water. Yet, lest the larger circumstances of the time be forgotten, the achievements of the Civil Rights era were quite fresh, and Southern California and the rest of the USA were still heavily segregated. Within this larger context the All American City’s highest school offered its students a vivid preview of Century 21 society decades before anyone gave it much thought. In those days kids at LHS lived with ‘diversity’ before it became a buzzword or political issue.

Like my old place, one feature the school lacked was a social system of the kind apparently familiar in other high schools before and since. The student body was too much in flux for anyone to set the tone of campus social life or establish a dominant style. There was a broad and odd assortment of groups, but no clear hierarchy reflecting prestige or status. Instead there were numerous official and unofficial groups, from established, official clubs like Rotary or Lettermen to off-campus entities like DeMolay or the Crips. I kept a low profile as a freshman, but as a sophomore made it to the NFL: the National Forensics League, aka Speech Club. Speech clubbers were a motley, nerdy bunch, but had fun traipsing around to competitions across the area, from Malibu to Whittier, so it was excellent for getting out of the house on Saturday afternoons a couple times a month. And two of our sharpest seniors qualified for that spring’s state tournament. Gail and Alfred made a good account of themselves, and the latter eventually parlayed his brilliant, outrageous sense of humor into a unique and highly successful career. (A final act at LHS, his 1976 valedictory address, would cement his legendary status, but you had to be there -YouTube didn’t exist yet.)

Over the next couple years my academic and social life grew apace. Patterns emerged that revealed strengths and weaknesses: I was a good reader and had a knack for drawing but lagged in math. My best classroom experiences came within well-established instructional programs led by excellent, highly professional teachers. They included strong writing practice and, as a senior, a great introduction to photography and a chance to work freely in mixed media in my third year of art. I’d already gotten a clear view of my limitations in math when the Algebra 2 teacher made me sweat for a C, a hard-fought victory. I began to grasp the gist of it, but brought up the rear in a small class. By then I’d also reached my limits as an athlete, though as a junior I had a couple good moments as JV quarterback, with my personal peak preserved in a photo that made the yearbook. (Funny to see now, since it looks like I tripped and fell out of the huddle, but that’s a story for another time.) Yet the best lessons on offer at LHS were still being learned.

The activity that most consistently brought me into contact with the world beyond the classroom was football. I’d learned the game on the playgrounds of my old hometown and become a devotee. When I first went out for the sport at ‘The Wood’ in 10th grade it was clear my enthusiasm far exceeded my skill level, but I did manage to hang on through a season spent watching more athletic classmates win the sophomore league championship. One factor I could do little about was being a late bloomer. At 15 I was 5’8” and weighed about 135 pounds, while some classmates stood 6’+ and weighed 220. So I had some catching-up to do, and finally got it started by hanging around the small, well-worn weight room. A skinny white boy desperate to bulk-up found a superb role model there - a senior who also happened to be my neighbor.

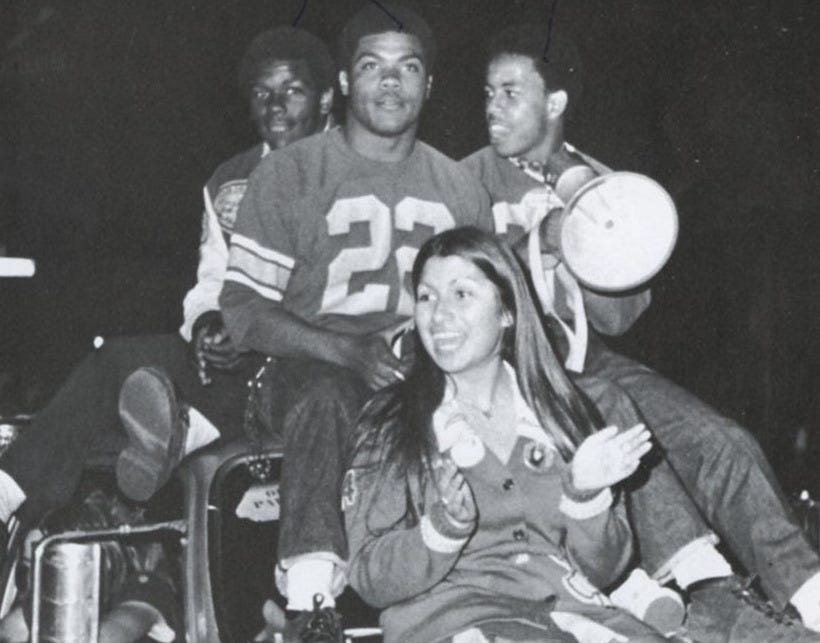

Farrell Mack, two grades ahead of me, was an all-league, two-way starter in football (halfback and cornerback) and shot putter on the track team. He had an impressive physique - I once saw him bench press 360 pounds - and guys worked to emulate him. In a time before single-sport specialization boosted the baseline of high school jock development he built a Greek god’s body through consistent, unflagging effort, and eventually won a scholarship to San Diego State. As puny and inconsequential an athlete as I was, Farrell was the opposite, but positive and encouraging to me, as was his brother Eddy, a classmate of mine and budding football star in his own right. Through their casual acceptance of the kid down the block I got a chance to rub shoulders with the black guys who formed the backbone of the varsity team. And so began the most valuable part of my secondary education.

Farrell and Eddie Mack (left rear) and friends

While our All American City muddled its way through the changes brought on by state-imposed division and demographic transformation, its high school enjoyed a historic run of athletic excellence -‘The Wood’ was loaded. Between 1975 and 1978 Lynwood High made it to the regional CIF championships in football, basketball and baseball (twice). The coaching was very good, but the deciding factor was the talent pool. The school had historically done well but never reached such heights before. Each of those teams was integrated and featured important contributions by white and Hispanic players, but the crucial elements were supplied by the black athletes. Three players on the championship basketball team of 1975 would win major college scholarships, including my classmate Tyren. When he sank the winning free throws for UCLA in a nationally televised game a few years later I could proudly say “I know that guy!” I also knew Todd, who pitched 14 straight victories for the ’78 baseball team and propelled it to the title game, and Jay, the younger kid down the block who later made it up through the Giants’ organization. My own singular contribution was to hold a clipboard on the sideline as we lost the football championship tilt in December of ’77, while a junior played ahead of me at the end of my senior season. Such is the fate of the second-stringer, to occupy the flip-side of gridiron glory. But even if Tony’s arm wasn’t that much better than mine, his athletic ability was clearly on another level - so I can still console myself with the knowledge that I played behind a guy who also happened to be a starting point guard and held down a spot in the pitching rotation. His leadership skills might’ve made the difference anyway, and there was never any doubt about his superiority as an athlete.

High school jocks are fortunate if something of value lingers when their glory days fade, something more than warm memories. As slight as my part in our team’s success was, I witnessed and participated in it firsthand. From almost five decades on it remains a great and profound experience, to have lived in a moment when a bunch of teenagers who might’ve easily avoided each other or been shunted-off to different destinations came together, almost by accident, and showed what they were capable of. That it took place in the midst of an awkward and often difficult social transformation is all the more to their credit. They couldn’t have done it unaided, though. The adults on hand - our coaches and teachers - shaped the results decisively. In my case the key factor was Rikki Valencia, who started influencing my future as soon as I walked into her art room as a freshman. Since I lacked any notable ability other than drawing it was a fortuitous break in my favor. Years later, having developed nothing much in terms of job prospects or social capital, I opted to follow her lead into teaching, and managed to stay employed and (more or less) sane for a working life that lasted about nine times longer than my stint in high school.

One thing I didn’t manage to draw from those four years was a sense of what most other people thought, felt or were motivated by, including terms of race and rank - at LHS those issues seemed moot. By the time I graduated my home life was down to my dad and myself. Being already in his 70s, he had little other than the most general bits of advice to pass along. So I was slow to realize that not everyone had had a chance to absorb the same lessons I did. In fact the locker room hadn’t been the only setting where my childish self-conceptions met reality head on. It happened repeatedly in the classroom, too - memorably so as a junior in that Algebra 2 class. I played catch-up there to a room full of girls, most of whom were black, with the senior among them soon on her way to Mount Holyoke. That didn’t actually seem exceptional at the time; among the other high achieving seniors on campus that year was my football buddy Theo, who was headed for the Air Force Academy. We’d first met in French class, where my aptitude for language proved flat-footed and I had to switch out to Spanish while he went on to greater parlez. And years after graduation I ran into my former classmate Vanessa at UC San Diego. That she’d been among the most popular and well-loved members of the LHS class of ‘78 didn’t matter much at that point. She’d already succeeded in politics as class president and then left it behind on her way to an MD. Of course Vanessa was special, not typical. But she also represented a range of talent, ability and good character I’d witnessed among black kids whose families wanted them to take advantage of previously closed opportunities. They were a testament to a greater collective potential that, having been stifled by racism for so long, was finally being allowed to flower. The kids that did that were my friends.

Now I know: there were people our age in other parts of the country, even other All American Cities, who learned different lessons. Of course it didn’t take me almost five decades to get a sense of that, but I’m still taken aback by it sometimes. I had gone on to spend the rest of the 20th century thinking they were all playing catch-up to those of us lucky enough to attend ‘The Wood’, but now that we’re well into the 21st century I’m not so sure. We’re in a different era, one in which racial tensions persist after having acquired new baggage even as some of the old burdens are put aside. My particular high school years remain etched in me in a way that renders a variety of otherwise common experiences a bit alien, and I’ve frequently noticed the deficit on my side. But being schooled where and when I was produced something unique and valuable that I’m hoping to preserve as I get old. I remain grateful, and am trying to keep it in view.

*******************************************

A project I’ve considered for a long while is an oral history of Lynwood and LHS focused on the pivotal decade of the ‘70s, something with a Studs Terkel flavor. Because, as unusual as it was and as much as it meant to me, there were always at least 2,000 other students there, and obviously our experiences didn’t overlap completely. Not long after high school I read Whatever Happened To The Class Of ’65?, and as the years went by it occurred to me that the same question could apply to LHS in an interesting way. So why not? One reason for this Substack (not just this post) is to test the feasibility of that project. So, DON’T TOUCH THAT DIAL! Please stay tuned for further developments in the New Year. And, if you were there, don’t be too surprised if I drop you a line…

Hey Tim,

The “Wood” definitely was an interesting place to attend high school. I too have fond memories of LHS and our time on the football team. I hope you do pursue this project.

If you go on to write a book, this piece would make an excellent introduction. Very well written.